Hughes, Pucovski, and cricket's concussion problem

Malcolm Conn was Cricket Australia's media manager when Phil Hughes tragically died. Ten years on, he traces what cricket has done to make the game safer.

Malcolm Conn is a former media manager at Cricket Australia, and veteran reporter of nearly 40 years. You can follow his work on BlueSky, Instagram, Facebook & LinkedIn.

I saw Phil Hughes fall face first onto the SCG pitch, and instantly knew he was in trouble.

Watching on the live stream as Cricket Australia’s Senior Media Manager, my office was 200 metres from the playing arena. By the time I had run down behind the stately old Member’s Pavilion and through a gap in the boundary fence, Hughes was on a motorised stretcher at the Paddington end of the ground.

With a white tablecloth held up to protect Hughes from the gaze of the public and media, Cricket Australia head doctor Dr John Orchard worked frantically on the fallen cricketer. “I’ve got a pulse,” I heard Orchard say.

This was bad. Really bad.

It was November 25, 2014 and Hughes, about to turn 26, was batting his way back into the national team with a controlled 63 for his Sheffield Shield side, South Australia.

Then he attempted a hook, went through the shot too quickly, and suffered a blow to the back of the neck just below the skull. That’s when time stopped.

Rushed to nearby St. Vincent’s hospital for surgery, there was hope overnight that Hughes would recover, but by morning it was clear that nothing more could be done.

His family agreed to keep Phil alive for another 24 hours so players from around the country could fly in to say goodbye. They said goodbye again a few days later at a funeral which swamped his tiny home town of Macksville, a dot on the map half way between Sydney and Brisbane.

After that unimaginable week of mourning, there was a determination amongst players and officials to ensure such a tragedy never happened again.

The billion dollar problem

Analysis across Australian cricket has found that a player at state or national level is hit in the head on average every two years. This equates to about 40 players a year.

Research shows that concussions occur every six to 10 blows, but there are also concerns about repeated head knocks which may not result in a concussion immediately, but could have a cumulative impact later in life.

In America, the National Football League (NFL) has paid out $1.2 billion to 1,600-plus athletes since a landmark 2015 settlement that promised to compensate former players who developed dementia and other brain diseases tied to concussions.

To preempt player injuries on that scale, Cricket Australia asked Professor Andrew McIntosh, an expert in racing collisions, to look at how concussions could be prevented in cricket.

“There are a couple of things we were looking at around materials, around testing methods,” McIntosh told Best of Cricket.

“We needed to know a little bit more about how concussion is occurring, to be confident that we're going to optimise helmets to prevent concussion.”

Improvements to modern helmets

Professor McIntosh’s work has resulted in changes to the equipment worn by batters.

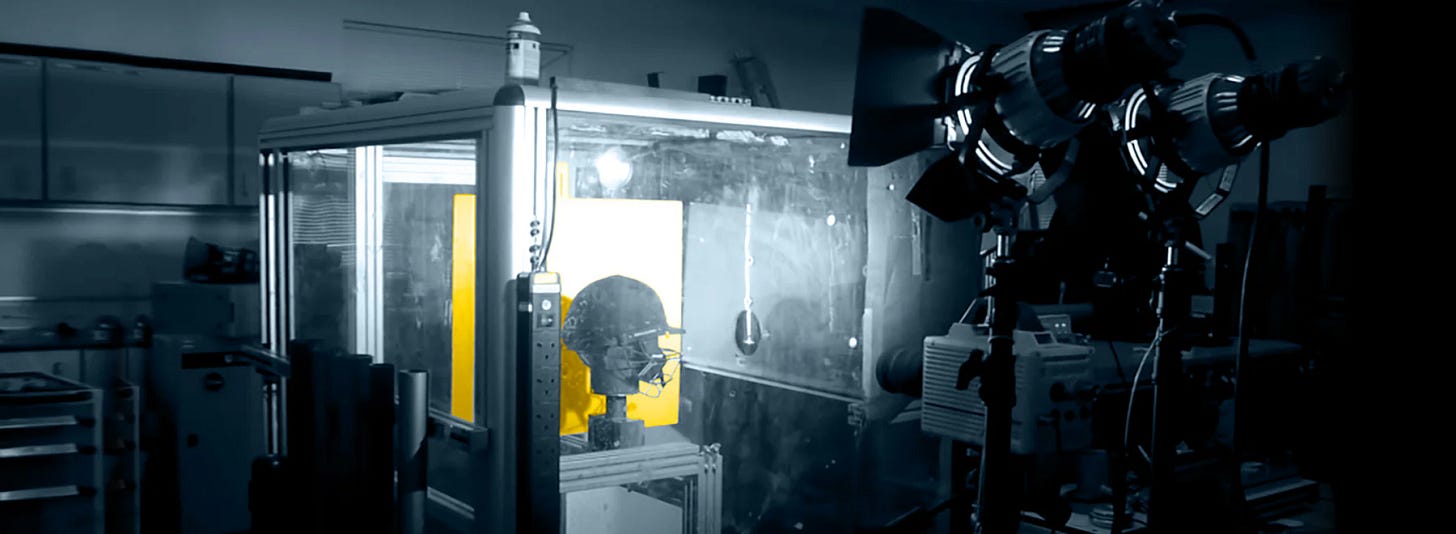

Helmets are tested by firing cricket balls out of air cannons at up to 80mph (130kph). This was used to improve the strength and size of grills, preventing the ball going through the seeing gap and making sure the grill was not pushed back into the test dummy’s face.

There was also significant research into making adequate neck protectors which could absorb the required impact. They have since been mandated as part of the British Standard which now governs helmets.

However, a concussion is much more difficult to manage than a bad hit. There are concerns that the shock - or energy - of a blow is simply transferred from the helmet to the skull and then the brain.

Video analysis of players being hit is used to assess the speed and angle of deliveries when players are diagnosed with concussion.

However, while it is clear that a player hit flush on the helmet is more likely to suffer concussion than one which receives a glancing blow, there is still no definitive data on how to identify and prevent concussions.

“Helmets save lives”

Matthew Hayden is a great defender of the helmet, as a protection for the forward press modern players often use.

“Helmets save lives,” Hayden said. “As soon as I go back and across [to a bouncer], I’m in a very stationary position and I’m pretty anchored on my back foot. If you press forward, you’re in a dynamic position. You can then press onto the back foot [to hook and pull].”

Tim Paine, Australia’s captain between 2018 and 2021, believes intent is a key factor in playing the short ball correctly in the modern era.

“I think the guys who play [bouncers] well have the mentality [that] they’re looking to score all the time, and then they’re in a better position because they’re looking to score,” Paine said. “They’re watching the ball a bit closer [and they’re] in a better position to make a decision a bit later.”

Helmets are built for comfort, not concussion prevention

UK helmet manufacturer Masuri has recently begun using three dimensional scanners and printers to make individually fitted helmets for players. A 360 degree scan is taken of the player’s head and a 3D printer makes what Masuri CEO Sam Miller says is a “customised internal padding set.”

The new helmet is not yet available to the public but is currently used by a number of Australian and English players, as well as two thirds of the Australian states and English counties.

Miller says the new helmet has been designed for better comfort and safety, but for all the research, there is no way of accurately determining a helmet’s capacity to reduce concussion.

“The difficult thing for us in terms of development of those products is there's no standard test that…will tell us whether it's better for concussion,” Miller said.

The unintended consequence of helmets

Ian and Greg Chappell, who spent most of their careers batting in caps in the 1960s and 1970s, believe that modern players are hit more often because of a false sense of security provided by helmets.

Both claimed they were only ever hit in the head once while batting, in both cases on wet wickets early in their careers. They offered the same advice; watch the ball and step inside it when it’s short, so it’s always on the leg side.

“At least if you miss the ball, it misses you,” Greg said. “We grew up pre-helmets, and it was important to do it properly.”

“The sad thing is with helmets in play, it’s an afterthought when coaching [how to bat], whereas in pre-helmet days it was one of the first things that you learnt. Now I see more people hit in a game than I saw in a career.”

Ian was “staggered” how much batting technique had changed in cricket when he saw highlights of Australia’s triumphant 1974-75 Ashes series. “In those days, batsmen predominantly went back and across, which was the way you were brought up,” Ian said.

“I was told as a young bloke that it’s what [Don] Bradman did, it’s what [Garry] Sobers did, and I thought, ‘Well, it was good enough for those two, it’s good enough for me.”

Will Pucovski has become the unfortunate poster boy for concussions in cricket. The talented Victorian batter has suffered at least 13 concussions in the last few years, and it seems to have unofficially ended his career at just 26.

Cricket Victoria and Pucovski’s legal representatives are currently in negotiations over how to settle his contract and what compensation there should be for potential future earnings. The outcome will have enormous implications for future claims by impacted players.

This is a fight that’s playing out across sports, as we saw with the NFL’s $1.2 billion (and growing) payout earlier.

There has been some significant progress in cricket, with Marnus Labuschagne becoming the first concussion sub in Test cricket five years ago. He replaced Steve Smith, who was struck on the neck by Jofra Archer at Lord’s in scarily similar circumstances to Hughes.

But, a decade after Hughes’ tragic accident at the SCG, cricket still has a fundamental problem with preventing concussions.

“Every sport is so different in terms of the concussion,” says Masuri’s Sam Miller, “If you compare, say, rugby or NFL to a cricket impact, they're just completely different. So there's a long way to go, I think, in understanding the link between helmet design and concussion.”

Editor’s note: An initial version of this story identified Professor McIntosh as having conducted research into Australian rules football. In fact, he is an expert on racing collisions.